In Defence of the Ripping Yarn

|

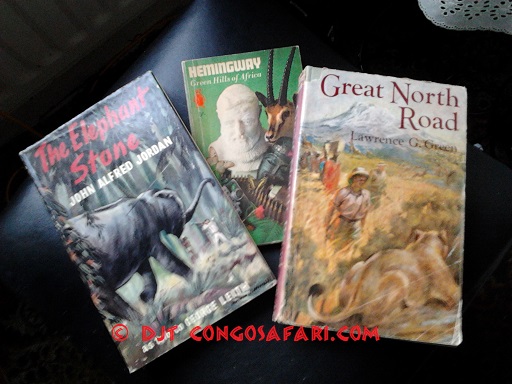

I recently read a PhD thesis about certain events in Central Africa. It is an interesting and useful document, worthy of a PhD. However, history is always written from a point of view and often a premise. History students are not scientists and their conclusions are not always mathematical deductions. The thesis started with the politically correct goal of investigating whether the perception of those events, by Europeans, was incorrect and prejudiced. It then collected and collated a large amount of data which, on the whole, seemed to confirm that the European perception was correct, but the author still concluded that it was incorrect. Perhaps this apparent contradiction was because the PhD student obtained more information than was actually cited in the thesis. The student interviewed many descendants of the people involved, and those interviews may have contributed to the student's conclusion. I think that the student should not have placed much historical value on interviews with people who had not even been born when the events took place. European and American travellers, adventurers and settlers in Central Africa sometimes left written and even illustrated eye-witness accounts. With respect to what they actually saw, those records are mostly accurate but their prejudices sometimes caused them to misinterpret what they saw. The indigenous peoples that they encountered typically recorded their history orally. Oral history cannot be entirely ignored but it has the obvious problem of events and characters being distorted or embellished from generation to generation. Also, the modern descendants of indigenous eye-witnesses now often have First World perceptions and values themselves, which must reduce their ability to accurately interpret their own oral history. Oral history must inevitably reflect what the oral historian feels that the past should have been, rather than what it was. Perhaps the most valid records are those that were written by policemen, anthropologists or historians who managed to interview indigenous eye-witnesses. Political correctness is all very well for political purposes but for historical correctness, we should regard written eye-witness records as the most reliable sources. Also, the interpretations of the events by European eye-witnesses should not be regarded as having any less validity than the interpretations by the descendants of eye-witnesses who only left an oral record. Logical deduction can largely filter out the prejudices, and sometimes the lies, of the writers. Sometimes, the truth appears so much like a ripping yarn from Boys' Own paper that historians tend to ignore it. An example is John Alfred Jordan's eye-witness account of a raid by leopard-men in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. Jordan was an adventurer who brought little material proof of his adventures out of Africa. He was a poacher, and of the poacher he said "He shot for profit. He had no home. He had no library wall to stud with the horns of kudu and rhino. He was in Africa for life, not for the season." (The "season" was, in the Edwardian era that was Jordan's heyday, England's spring and summer, when the upper classes congregated for social gatherings and sporting events. They typically spent most of the season in London but as it coincided with the closed seasons for hunting and shooting in Britain, shooting trips to India or Africa were popular. Jordan was admitting that he was not an upper class sportsman. His was not the Kenya of the Muthaiga Club, polo and [alleged] Happy Valley orgies.) He kept an old Belgian Congo elephant hunting licence and some photographs but there is not much else, apart from some reminiscences by his friend Edgar Beecher Bronson in the 1910 book In Closed Territory. That is enough to place Jordan in East and Central Africa early in the twentieth century, a time when it was not possible for a European to avoid seeing things that other Europeans would regard as strange and even unbelievable. Jordan may have sometimes misinterpreted what he saw but he had a tendency NOT to romanticise his adventures for the benefit of his readers. The animals he shot sometimes suffered horrendously. He believed that cannibals existed but in spite of all of his years among barely contacted tribes in Kenya, German East Africa, Uganda, the Belgian Congo and Angola, even among tribes with a reputation for cannibalism, he never claimed to have seen any evidence of it, except for the filing of teeth, which many Europeans of the era mistakenly thought indicated cannibalism. To the best of his ability, he was an honest witness. Men like John Alfred Jordan were not just adventurers. They were sometimes the sole eye-witnesses to record events of significance, for the benefit of both Europeans and the descendants of Africans who, at the time, only had an oral history. |

COPYRIGHT DJT text © September 2019 : No material on this site may be copied by any means, without the author's permission.